Top 10 Inspirational Persons in the World for Students

Students grow when they see a path they can follow. Social–cognitive research shows that confidence in one’s ability—self-efficacy—shapes how much effort learners invest and how long they persist when work gets hard.

Growth-mindset studies add that students who believe abilities can improve through practice keep going and recover from setbacks faster.

Two more pillars help: grit and high-quality practice. “Grit” predicts long-term effort toward goals, and “deliberate practice”—goal-focused, feedback-rich repetition—builds skill over time. Role models make those ideas concrete. When students read about real people who trained with purpose and stayed with difficult goals, they can picture the steps, not only the finish line. Carefully chosen exemplars lift motivation; poorly chosen “unreachable superstars” can do the opposite.

Context matters. Positive role models who share a learner’s identity or background can boost belonging in fields where students feel under-represented. Reviews in psychology and education show this effect for girls and women in STEM and for other under-represented groups.

The need is real: recent international assessments reported lower performance trends for many 15-year-olds, with wide gaps between and within countries. Students benefit from stories that make effort, strategy, and hope practical again.

Table of Content

- Top 10 Inspirational Persons in the World for Students

- How to use this guide

- The Top 10: Brief profiles, lessons, and classroom tie-ins

- From inspiration to daily action: a simple plan

- Quick classroom toolbox

- Why this mix works

- Concise profiles for reference

- Conclusion

- FAQs

How to use this guide

Read each profile with one question in mind: What habit or choice can I try this week?

Use the “study takeaways” to shape daily routines such as short sessions, specific goals, and feedback.

Teachers can pair a profile with a quick activity—reflection, short speech analysis, or a one-page plan.

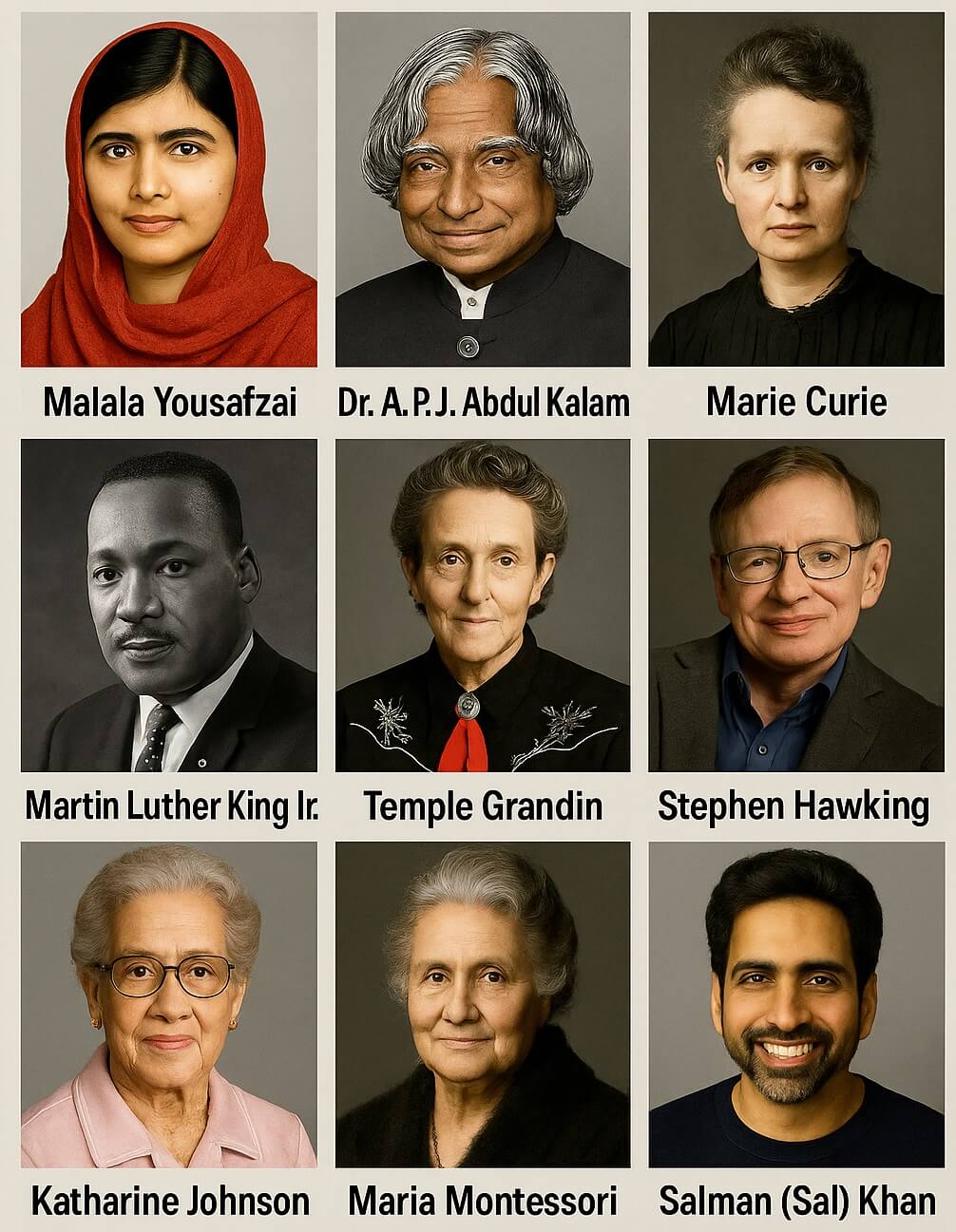

The Top 10: Brief profiles, lessons, and classroom tie-ins

1) Malala Yousafzai — student voice and courage

Why students connect

Malala spoke up for girls’ education as a young teenager and continued her advocacy after surviving an attack. At 17 she became the youngest Nobel Peace Prize laureate. Her work shows that a student voice can move the world when it stays rooted in purpose and learning.

Study takeaways

• Keep a learning journal. Note one idea from class that matters beyond school.

• Practice short persuasive speeches that use facts and clear structure.

Classroom tie-ins

Read excerpts from Malala’s UN address and identify claim, evidence, and call-to-action. Then write a 150-word speech on a local school issue.

2) Dr. A. P. J. Abdul Kalam — science, service, and humility

Why students connect

Known as the “People’s President” of India and the “Missile Man,” Dr. Kalam led major national projects after training in aeronautical engineering. He stayed close to students, speaking about curiosity, values, and national development long after his presidency.

Study takeaways

• Break a big goal into stages: concept, prototype, test, share.

• Write “lessons learned” after each test; treat errors as data.

Classroom tie-ins

STEM project cycle: set a simple engineering problem, build a low-cost prototype, run a three-point test, present results in a one-slide briefing.

3) Marie Curie — quiet focus, long horizons

Why students connect

Curie remains the only person with Nobel Prizes in two different sciences—Physics (1903) and Chemistry (1911). Her path shows steady work, careful methods, and service to others, including wartime radiology units. Students see a scientist who kept going for years, step by step.

Study takeaways

• Schedule “deep-work” blocks free from alerts.

• Keep a results log: question → method → finding → next step.

Classroom tie-ins

Analyze a short section of Curie’s Nobel lecture. Ask students to label the research question, evidence, and conclusion in plain language.

4) Nelson Mandela — education as a public good

Why students connect

Mandela framed education as the lever that changes lives and communities. His addresses highlight schooling as the strongest tool for social progress. Students learn that study is personal and civic at the same time.

Study takeaways

• Connect a subject to a community benefit. Write one sentence: “When I learn X, I can help with Y.”

• Practice active empathy in group work—rotate roles, listen, then respond.

Classroom tie-ins

Short research task: collect two local examples where learning improved health, safety, or income, and present them with one statistic each.

5) Martin Luther King Jr. — clear language and moral focus

Why students connect

King’s speeches model plain words, rhythm, and vivid images that move listeners. The “I Have a Dream” address remains a standard text in rhetoric courses and citizenship lessons. Students can learn structure, cadence, and the power of precise phrasing.

Study takeaways

• Edit for clarity: replace abstract terms with concrete nouns and active verbs.

• Practice three-part structure: problem, promise, and action step.

Classroom tie-ins

Annotate a short passage from the National Archives transcript. Label repetition, metaphor, and parallelism. Then students craft a 90-second speech using the same devices.

6) Temple Grandin — different minds, stronger solutions

Why students connect

Grandin, a professor of animal science, improved humane livestock handling and speaks openly about autism and learning differences. Her story shows that a “different thinker” can redesign systems and mentor others.

Study takeaways

• Build study methods that match your brain—visual diagrams, tactile models, or short audio summaries.

• Use checklists to stabilise routines under stress.

Classroom tie-ins

Design-thinking sprint: students sketch a layout that reduces stress for animals or people in a crowded space, explaining the sensory logic behind each choice.

7) Stephen Hawking — curiosity under limits

Why students connect

Hawking advanced cosmology for decades while living with motor neurone disease. He held the Lucasian Professorship at Cambridge and wrote A Brief History of Time, a gateway text for many young readers. The message lands simply: keep asking questions; keep learning.

Study takeaways

• Turn each chapter into a list of genuine questions.

• Teach back one concept to a friend in two minutes.

Classroom tie-ins

Concept-map black holes or cosmic expansion in everyday terms, then compare to a textbook paragraph to refine accuracy.

8) Katherine Johnson — precision and trust

Why students connect

Johnson’s orbital calculations for NASA built trust at the highest stakes—astronauts asked for her verification before flight. Her legacy pairs excellence with teamwork and quiet confidence.

Study takeaways

• Show your working: write clean steps, label units, and run a second check.

• Build a “buddy review” habit before submission.

Classroom tie-ins

Students compute and cross-check a simple projectile problem with two methods. They sign off on each other’s work before turning it in, mirroring mission-readiness culture.

9) Maria Montessori — independence through practice

Why students connect

Montessori pioneered a child-centred method that builds independence through choice, hands-on materials, and respect for concentration. Her international association continues her work across schools worldwide.

Study takeaways

• Use “work cycles”: set a 25–40 minute task, then a short break; protect focus during each cycle.

• Organise materials the same way each day to reduce friction.

Classroom tie-ins

Create a self-guided station with clear task cards and simple materials. Students pick any two stations and record what they learned at each.

10) Salman (Sal) Khan — open learning for everyone

Why students connect

Sal Khan started by tutoring a cousin and grew that act into a nonprofit with a mission: free, high-quality learning for any student with internet access. The model supports mastery and teacher partnership.

Study takeaways

• Practice until you can explain a topic without notes.

• Use short quizzes to find gaps, then target practice on weak skills.

Classroom tie-ins

Flipped-lesson pilot: watch one short video at home, try six practice items in class, then write a reflection on mistakes and fixes.

From inspiration to daily action: a simple plan

Set goals that fit real life (weekly)

Pick one subject and one micro-goal such as “master factoring quadratics Level 1.”

Plan three short sessions for that goal this week.

This mirrors deliberate practice: clear target, focused reps, quick feedback.

Train your mindset (daily)

Replace “I can’t do this” with “I can’t do this yet; next step is ___.”

Track effort and strategy in a two-line reflection after homework.

These moves build a growth-oriented story linked to concrete actions.

Build staying power (weekly)

Choose one “hard thing” to keep for eight weeks—instrument scales, coding drills, or a sport skill.

Log minutes, not outcomes. Grit grows through steady effort toward one aim.

Use models wisely (monthly)

Rotate who you study: one scientist, one civic leader, one local mentor.

Pick role models who feel attainable and relevant to your context. When the fit is better, motivation is stronger.

Quick classroom toolbox

Role-model one-pager

Students write a one-page brief covering background, one key obstacle, one repeatable habit, and one class activity to try. Pair each brief with a cited source when assigning.

Speech lab (language and civics)

Use short primary-source excerpts from King or Mandela. Students mark rhetorical devices and write a short address on a school issue, using the same devices.

STEM practice loop

Adopt Johnson’s “show your working” norm across maths and science. Students submit solution steps and a partner verification panel.

Independent work cycles

Borrow Montessori’s structure to run silent work blocks with clear task cards. Debrief with two sentences: “What I tried” and “What I’ll change.”

Why this mix works

Identity and belonging

Students from varied backgrounds can see someone who feels familiar and credible. Research links such exposure to higher engagement, especially in under-represented groups.

Skill and structure

The list blends scientists, civic leaders, educators, and builders of learning platforms. That range keeps lessons grounded in daily study habits, not distant fame.

Evidence and practice

Each profile ties to study behaviours supported by research on mindset, practice, and persistence.

Concise profiles for reference

Malala Yousafzai — Nobel Peace Prize laureate at 17; advocate for girls’ education.

A. P. J. Abdul Kalam — aerospace scientist; India’s 11th President; mentor to youth.

Marie Curie — Nobel laureate in Physics and Chemistry; model of sustained inquiry.

Nelson Mandela — framed education as a lever for social change in addresses and campaigns.

Martin Luther King Jr. — landmark speeches; primary sources available for close reading.

Temple Grandin — professor and advocate; shows the value of different cognitive styles.

Stephen Hawking — Cambridge physicist; accessible science writing that sparks curiosity.

Katherine Johnson — NASA mathematician; trusted for high-stakes verification.

Maria Montessori — physician-educator; global method focused on independence.

Sal Khan — nonprofit founder; mastery learning and open access at scale.

Conclusion

Students do better when inspiration points to action. The figures above offer steady habits: plan work in short cycles, write out thinking, seek feedback, speak with clarity, and care about others.

Pair those habits with evidence-based tools—growth mindset language, deliberate practice, and grit built over weeks—and classrooms change in quiet but durable ways.

FAQs

How should I choose a role model for a mixed-ability class?

Offer a menu. Include a scientist, a civic leader, and a local mentor. Let students pick one profile and state one skill they want to try. Choice and fit raise engagement.

What if students say, “I’ll never be like that person”?

Shift the focus from who to what they did. Highlight one habit and rehearse it for a week. Share quick wins at the end of the week. That keeps attention on practice, not status.

Are historical figures still relevant to teenagers?

Yes, when we connect their choices to present-day tasks such as note-taking, project planning, clear speech, and teamwork. Use primary sources for authenticity and short tasks for transfer.

What study routine matches this article?

Three sessions per week per target skill, 25–40 minutes each, with a two-line reflection after every session. Add one peer check each week to build accuracy.

Where can students read more from credible sources?

Look for official institutional pages such as Nobel Prize biographies, NASA profiles, university faculty pages, national archives, and established educator associations.

Motivational Topics