Evidence-Based Study Skills: Question Better, Learn Faster, Remember Longer

You don’t need more hours. You need better questions and smarter study moves. Strong questions pull ideas out of hiding, and proven techniques lock them in memory.

This guide blends both—questioning methods that spark insight and research-backed habits that make learning stick. The aim is practical: use it today for class, exams, work projects, or self-study—no fancy tools required.

Who this helps

-

School and university students who want higher recall with less re-reading

-

Working learners who study for certifications after a full day

-

Teachers and mentors who want simple routines to coach learners

What “evidence-based” means here

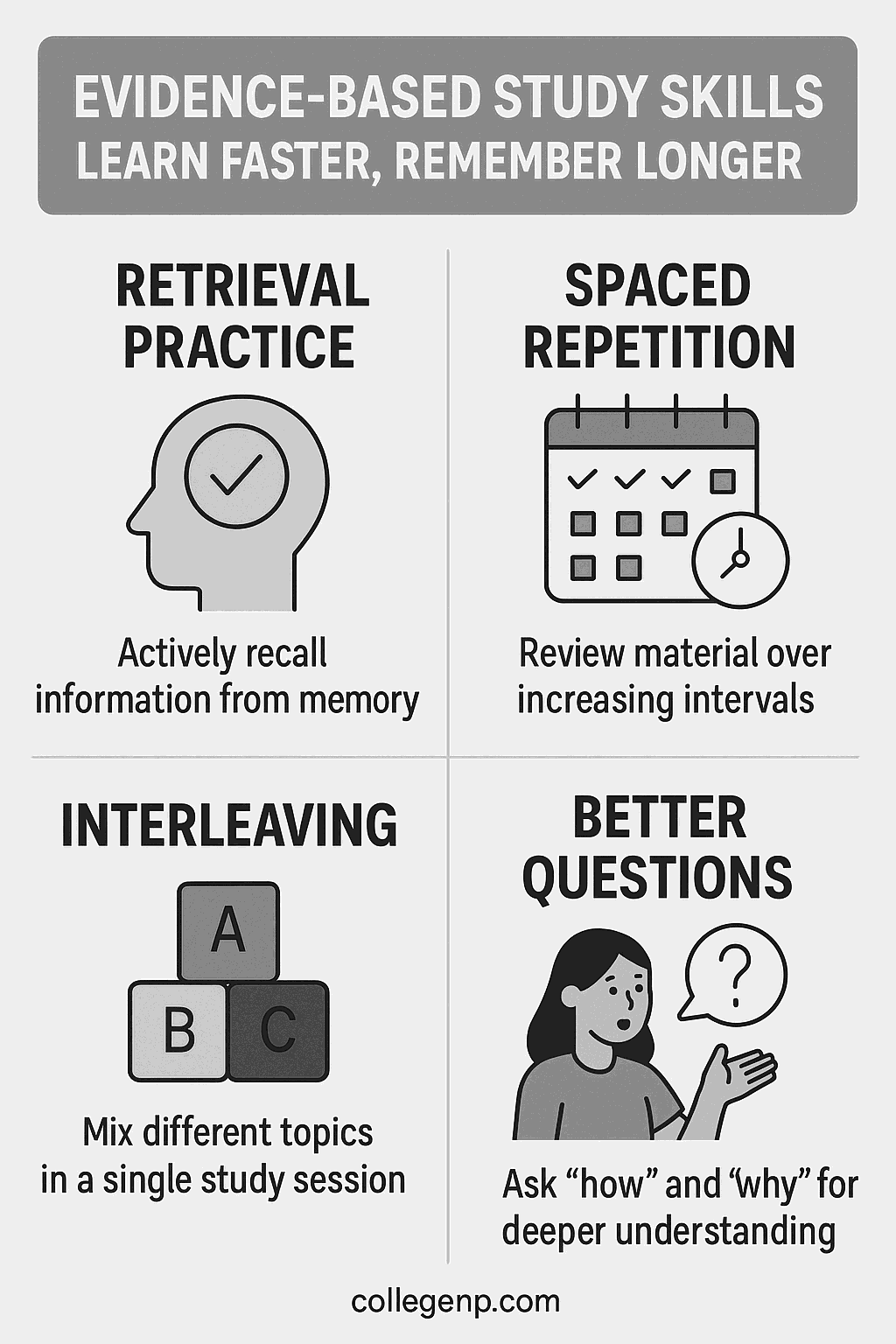

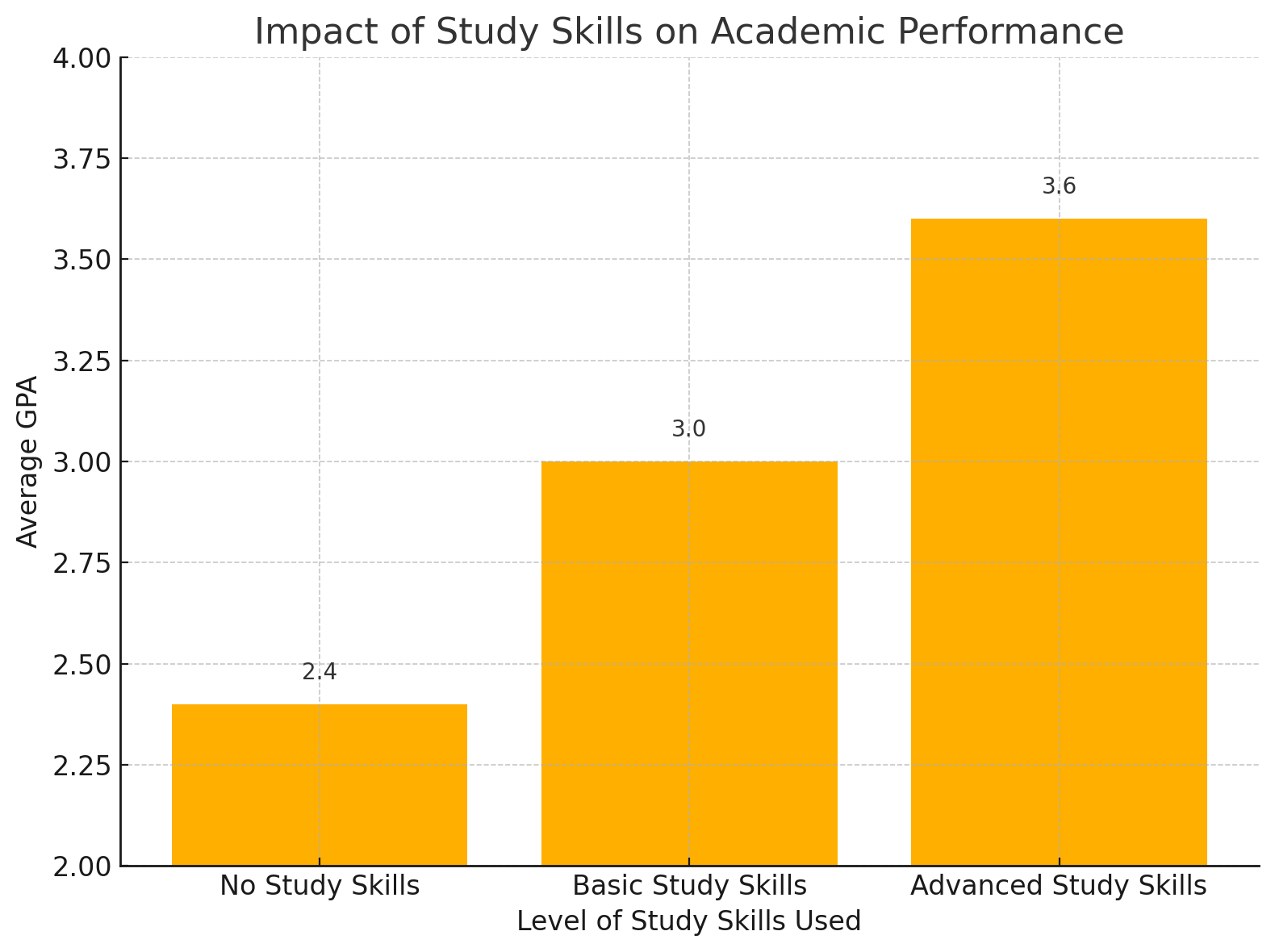

Every core technique below appears in peer-reviewed reviews or high-quality studies. The strongest effects come from:

-

retrieval practice (self-testing),

-

spacing (study, leave it, return later),

-

interleaving (mix problem types),

-

dual coding and effective multimedia,

-

good notes and active reading,

-

habit tools like “if-then” planning.

See the sources under each section and the reference list at the end.

The Question-First Mindset

Ask to retrieve, not to recite

A good question forces your brain to pull information from memory. That pull is “retrieval practice,” and it measurably boosts long-term learning far beyond re-reading. Large reviews and classroom studies show medium-to-large gains when learners test themselves during study.

A simple script for any topic

Use these prompts on flashcards, in a notebook margin, or aloud:

-

What are the key claims?

-

What evidence supports each claim?

-

Where does this fail? Exceptions?

-

How would I teach this in 60 seconds?

-

Which formula, rule, or diagram applies here—and why?

Such prompts map neatly onto retrieval and elaboration. They push you past recognition into recall, which cements memory.

Socratic questioning, used kindly

Structured questioning can improve critical thinking in professional education when it stays respectful and learner-centered. The research base is growing across medicine and allied fields; use it to probe assumptions and reasoning chains, not to embarrass.

Retrieval Practice: The strongest study move

What it is

Ask yourself to recall ideas from memory—no notes, no book—then check. Repeat across days.

Why it works

Testing doesn’t only measure learning. It creates it. Learners who practice recall (free recall, short-answer, essay, or well-built quizzes) retain more than those who re-read or make only concept maps. The effect holds across classrooms, topics, and ages.

Quick ways to apply

-

Two-column recall: cover notes, write what you remember, then compare.

-

One-minute brain dump at the end of a study block.

-

Teach a blank page: explain the idea as if to a friend, from memory.

-

Low-stakes quizzes you write for yourself.

Meta-analysis shows practice tests outperform re-study across many conditions.

Spaced Repetition: When you study matters

What spacing does

You revisit material with gaps between sessions. Memory strengthens when practice is spread out, not crammed. Reviews across decades show clear benefits for long-term retention.

How to time your reviews

A large study modeling “best” gaps suggests this rule of thumb: plan the first review at roughly 5–20% of the time until your exam or final use. Example: if your test is 30 days away, review in about 2–6 days, then stretch intervals.

A simple weekly cycle

-

Day 1: learn + short recall

-

Day 3: quick test

-

Day 7: mixed questions

-

Day 14 and Day 30: short refreshers

Learners often feel that massed study works better. That feeling misleads. Studies show a “stability bias”—we overestimate what we’ll remember and underrate spacing.

Interleaving: Mix problems to build flexible skill

What it is

Alternate problem types or concepts within a session. Instead of AAA BBB CCC, go A-B-C-A-C-B.

Why it helps

Mixing problems improves discrimination—spotting which method fits a given question—and aids transfer. Lab and classroom studies in math and category learning show higher test scores with interleaving than with blocked sets.

How to apply

-

Create small mixed sets: definitions, worked examples, and practice items from different chapters.

-

After solving, label why you chose each method.

-

Pair with spacing: rotate topics across sessions.

Dual Coding and Multimedia: Learn with words and visuals

The idea

Combine verbal explanations with relevant visuals (diagrams, timelines, concept sketches). This taps verbal and visual systems together.

What the evidence says

Richard Mayer’s multimedia research outlines principles that help learners build mental models—signal key parts, segment complex processes, match words with pictures, and avoid clutter.

Try this today

-

Convert dense paragraphs into a one-screen diagram.

-

Pair a short caption with each step in a process drawing.

-

For formulas, show a labeled sketch of the situation next to the equation.

Note-Taking That Pays Off

Longhand vs. keyboard

Typing pushes many students toward transcription. Handwritten notes slow you down and prompt more processing, which links ideas. Across three studies, longhand note-takers answered conceptual questions more accurately than laptop users.

Guided notes help

Students’ self-written notes often miss key points. Reviewing a complete, accurate set of instructor notes—or combining them with your own—improves recall.

A clean structure

-

Cornell layout (cues, notes, summary)

-

Headings and subheadings that mirror the syllabus

-

Margins for “exam-style” questions you can answer later

Protect attention in class

Laptop multitasking hurts your learning and the learning of nearby peers. If you must use a device, close unrelated tabs and turn off notifications.

Read to Learn, Not to Re-read

Active reading beats passive scanning

Try SQ3R for textbooks: survey, question, read, recite, review. The steps match what memory research supports—preview structure, set questions, then retrieve.

A five-minute routine

-

Skim headings and figures; predict the big idea.

-

Write 2–3 questions before you read.

-

Read one section; then look away and answer your questions.

-

Mark gaps, return to the text, and fix weak spots.

-

Summarize one sentence per section from memory.

Retrieval-focused writing (a short free-response recap) often beats concept mapping for durable learning of science text.

Build a Week That Sticks

The 3–2–1 pattern

-

Three focused sessions on priority topics

-

Two mixed review blocks (interleaved, spaced)

-

One longer “teach it” session: explain everything you can recall on paper

Plan with “if-then” cues

Link study actions to cues: “If it’s 7:30 pm and I’m at my desk, then I open the problem set and do five items.” Such plans raise follow-through across many goals, with medium-to-large effects in meta-analysis.

Attention, Energy, and Learning

Sleep supports memory

Across reviews, sleep helps consolidate new learning. Short naps can aid perceptual and motor skill learning; full nights support broader memory systems. Aim for consistent bedtimes, dark rooms, and phone-free wind-down time.

Move your body

Aerobic activity links to better executive function and academic performance in children and benefits adults as well. Short walks between study blocks lift mood and focus.

Common Myths to Drop

“I’m a visual/auditory learner”

Large reviews find no strong support for matching instruction to a declared “learning style.” Pick techniques that fit the material and your goals—use visuals for visual ideas, words where precision matters.

“Re-reading equals mastery”

Re-reading builds fluency illusions. Retrieval and spacing feel harder, yet they win on delayed tests.

Mini-Workbook: 30-Minute Study Sprint

Setup (5 minutes)

-

Write your target question or skill.

-

List three potential sub-questions.

-

Open only the needed material.

Learn (15 minutes)

-

Read one section or watch one segment.

-

Sketch a quick diagram or example.

-

Solve one representative problem.

Retrieve (7 minutes)

-

Close materials.

-

Brain dump key points and steps.

-

Answer your sub-questions from memory.

Review (3 minutes)

-

Check gaps, annotate notes, make two flashcards.

-

Schedule the next review in your calendar (spaced).

Case Snapshots (composite examples)

Intro biology

A learner swaps nightly re-reading for a three-day cycle: read diagrams with labels, test with short free-response, then mix old and new topics. Scores rise two grade bands over a month. This fits the combined gains from retrieval, spacing, and interleaving.

Accounting certification

The candidate writes “if-then” cues for weekday evenings and uses mixed problem sets. Missed questions become next week’s flashcards. Completion rate jumps, and retention holds. The plan mirrors evidence for if-then planning and practice testing.

Nursing pharmacology

Handwritten drug tables plus “teach a blank page” on mechanisms. Short quizzes every other day. Stronger recall aligns with longhand note findings and the testing effect.

Teacher Corner

Design for effort, not ease

-

Start classes with two retrieval questions from the last lesson.

-

Interleave practice problems across units.

-

Offer partial instructor notes that highlight structure; ask students to fill key gaps.

-

Use low-stakes quizzes for feedback, then revisit items next week.

These moves reflect classroom evidence for test-enhanced learning, benefits of interleaving, and guided notes.

Quick Start Checklists

Five moves for this week

-

Replace one re-reading block with a 10-minute recall session.

-

Schedule two spaced reviews on your calendar.

-

Convert one page of notes into a diagram.

-

Mix three old problem types into tonight’s practice.

-

Add one “if-then” plan to your routine.

Red flags

-

Endless highlighting with no recall

-

All practice from one chapter only

-

All-nighter cramming without spaced follow-ups

-

Multitasking on a laptop during lectures

Ethics and Academic Integrity

Use these methods to learn, not to cut corners. Cite sources in assignments. When in doubt, ask your instructor what counts as permitted collaboration or tool use.

Final Thought

Better questions create the pull. Retrieval, spacing, and interleaving provide the structure. Add visuals and clean notes, plan with if-then cues, protect sleep and movement, and you’ll feel learning become steadier and calmer. Pick one move, try it tonight, and build from there.

FAQs

How many practice questions should I do per session?

Stop when accuracy stays high on mixed items, not on one type. A small, mixed set forces method choice and aids transfer, which improves later performance.

Is highlighting useless?

Highlighting can mark targets, yet recall drives learning. Turn highlights into questions or flashcards and test yourself across days.

What’s a fast way to start spacing without an app?

Use a calendar. First review two days after study, again one week later, then at two and four weeks. Adjust based on how tough the topic feels. The gap-to-exam rule of thumb helps.

Are concept maps bad?

They can help organize ideas. For durable memory, retrieval practice outperforms concept mapping on delayed tests, so pair the two: map then recall from a blank page.

Do I need to give up my laptop in lectures?

Not always. If you use it, disable distractions and paraphrase ideas instead of transcribing. Be mindful that multitasking harms comprehension for you and neighbors.

Study Tips Study Motivation