How to Study for Exams When You Have No Time

You have a deadline, limited hours, and a syllabus that feels long. You still have a path that works. The plan below favors practice testing, short spacing, smart mixing, and sleep after study.

These methods come from well-known research and practical guidance from university learning centers. They help when minutes matter and you need recall, not vague familiarity.

Use this as a short, direct playbook for the final 24–72 hours. Apply the steps in blocks. If you are working or traveling, run shorter loops during breaks. We recommend this plan to learners who ask for last-minute study tips grounded in evidence and everyday practice.

Table of Content

- How to Study for Exams When You Have No Time

- What Works When Time Is Short

- Rapid Triage: Aim Your Minutes at What Scores

- The 90–120 Minute Crisis Loop (Repeatable Block)

- Why Practice Testing Comes First

- How to Compress Spacing When Hours Are Limited

- How Mixing Helps on Test Day

- Use Cornell Notes for Faster Self-Quizzing

- Keep Your Brain Online: Sleep, Stress, Movement, Focus

- Subject-Specific Fast Tracks

- Micro-Routines You Can Run Tonight

- Common Traps and Better Swaps

- Use Time Pressure Instead of Fighting It

- Seven Takeaways You Can Use Tonight

- Practical Example: One Evening for a Mixed Exam

- FAQs

What Works When Time Is Short

Across large reviews, three methods stand out: practice testing (active recall), spaced practice, and interleaving. Rereading and highlighting alone sit lower in value. With little time, you can compress spacing into shorter gaps. Sleep after study still helps memory more than another late-night reread. These points appear again and again across journals and teaching centers.

Keywords to keep in mind: how to study for exams when you have no time, last-minute study tips, active recall, practice testing, spaced practice, interleaving, Cornell notes, exam anxiety, sleep and memory, phone distraction, STEM problem practice.

Rapid Triage: Aim Your Minutes at What Scores

Step A:

Predict questions. Open the syllabus, lecture outlines, assignment themes, and any review sheet. Add two or three past papers if you have them. Draft 8–12 likely questions in your instructor’s style. Keep them short and specific. This single step improves focus and matches how many teaching centers advise you to prepare.

Step B:

Tag the high-yield set. Pick three scoring clusters for the next block:

-

core definitions or formulas,

-

“classic” problem families or themes,

-

one idea you keep missing.

Step C:

One-line answers from memory. For each predicted question, speak or write a one-line answer without notes. Mark red (cannot answer), amber (partial), green (solid). That color map drives your next loop. University handouts endorse self-questioning because it creates retrieval, not passive exposure.

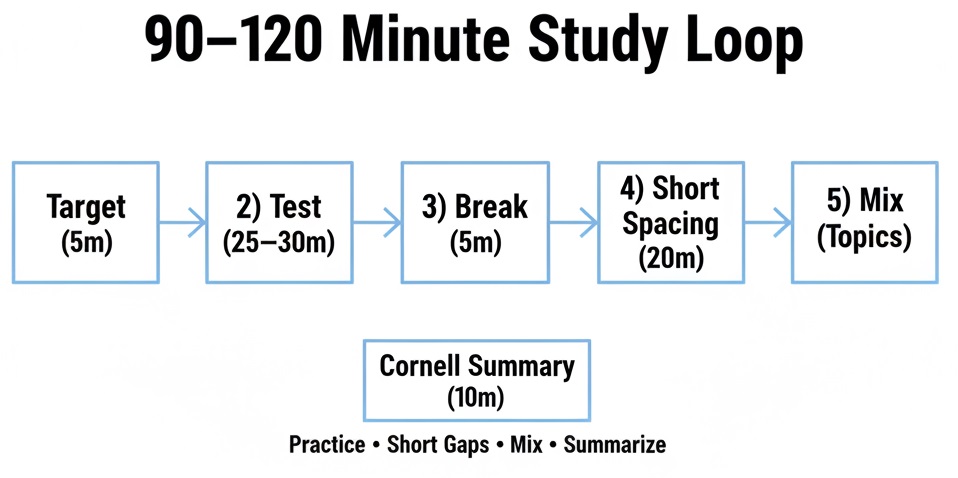

The 90–120 Minute Crisis Loop (Repeatable Block)

This loop fits a short evening or a long commute. You can run it once, rest, and run it again in the morning.

-

Targeting (5 minutes) - Choose the top three items from your triage board. Write them at the top of a page.

-

Practice testing (25–30 minutes) - Answer your predicted questions without notes. Solve 6–10 problems. Recite key steps or proofs out loud. Check answers quickly and record the exact miss (definition, step, or cue). Research on retrieval shows that testing yourself grows memory more than extra reading, especially after a delay.

-

Micro-break (5 minutes) - Stand, stretch, walk the hall, or get water. Short activity bouts help attention and school outcomes. Keep it light.

-

Compressed spacing pass (20 minutes) - Return to the same items after a short gap. Even small gaps beat a single massed session. This helps you hold material until test time.

-

Interleaving burst (10 minutes) - Switch to a related topic or problem type. Mixing helps you pick the right method under time pressure. Many studies show gains when similar concepts are mixed, not blocked.

-

Cornell conversion (10 minutes) - Turn today’s notes into a Cornell page: cues on the left, lean notes on the right, a 4–6 line summary at the bottom. You now have prompts for tomorrow’s quick quiz. The Cornell method is widely taught and easy to learn.

This single loop bundles the strongest tools—retrieval, spacing, mixing, and structured prompts—into a plan you can repeat.

Why Practice Testing Comes First

When you read a chapter again, the text looks familiar, and the brain “feels” like it knows it. Exams do not ask for that feeling; they ask for production. Practice testing forces production.

Studies across many subjects show larger gains from self-tests than from extra reading. Make simple prompts that mirror the exam: “Explain X in two lines,” “State and apply formula Y,” “Compare A and B in three points,” “Solve this past item under five minutes.”

Quick ways to build tests for yourself:

-

Turn each header into a question.

-

Convert bold terms into “What is…?” or “When do we use…?”

-

Copy two items from a past paper and answer without notes.

-

When stuck, write the missing step in one short line, then retest it after a short gap.

How to Compress Spacing When Hours Are Limited

Standard spacing spreads across days. You do not have that luxury, but you still can split study into two short passes tonight and one pass tomorrow morning.

The research base on spaced practice is large and points to gains in retention across many tasks. A short gap still beats no gap. Use timers so the second pass does not vanish from your plan.

A simple pattern:

-

Pass 1 at 7:00–7:30 pm (practice testing).

-

Micro-break to move and reset.

-

Pass 2 at 8:00–8:20 pm (second retrieval on the same set).

-

Morning review at 6:45–7:00 am (third retrieval with two new questions).

How Mixing Helps on Test Day

On many exams, the first challenge is to choose the right approach. Mixing related topics during study helps you notice what makes them different.

That way you do not apply the wrong formula or concept under pressure. Studies with math and concept learning show that interleaving improves final test scores when items look similar on the surface but need different moves.

How to mix without losing focus:

-

In math: rotate three problem families (A, B, C).

-

In history or psychology: switch between two theories and explain one key difference after each question.

-

In business or law: alternate case types and ask, “Which rule fits this case and why?”

Use Cornell Notes for Faster Self-Quizzing

You do not have time to rewrite a notebook. A Cornell page is faster to make and faster to test. Draw a narrow cue column on the left. Fill it with questions, formula cues, or trigger words. Keep short lines on the right. Write a short summary at the bottom. Many university pages teach this format because it keeps review active and helps short reviews stack across the week.

Two quick Cornell moves for you:

-

After a 25-minute block, write five cue questions on the left.

-

Before sleep or in the morning, cover the right side and answer from memory.

Keep Your Brain Online: Sleep, Stress, Movement, Focus

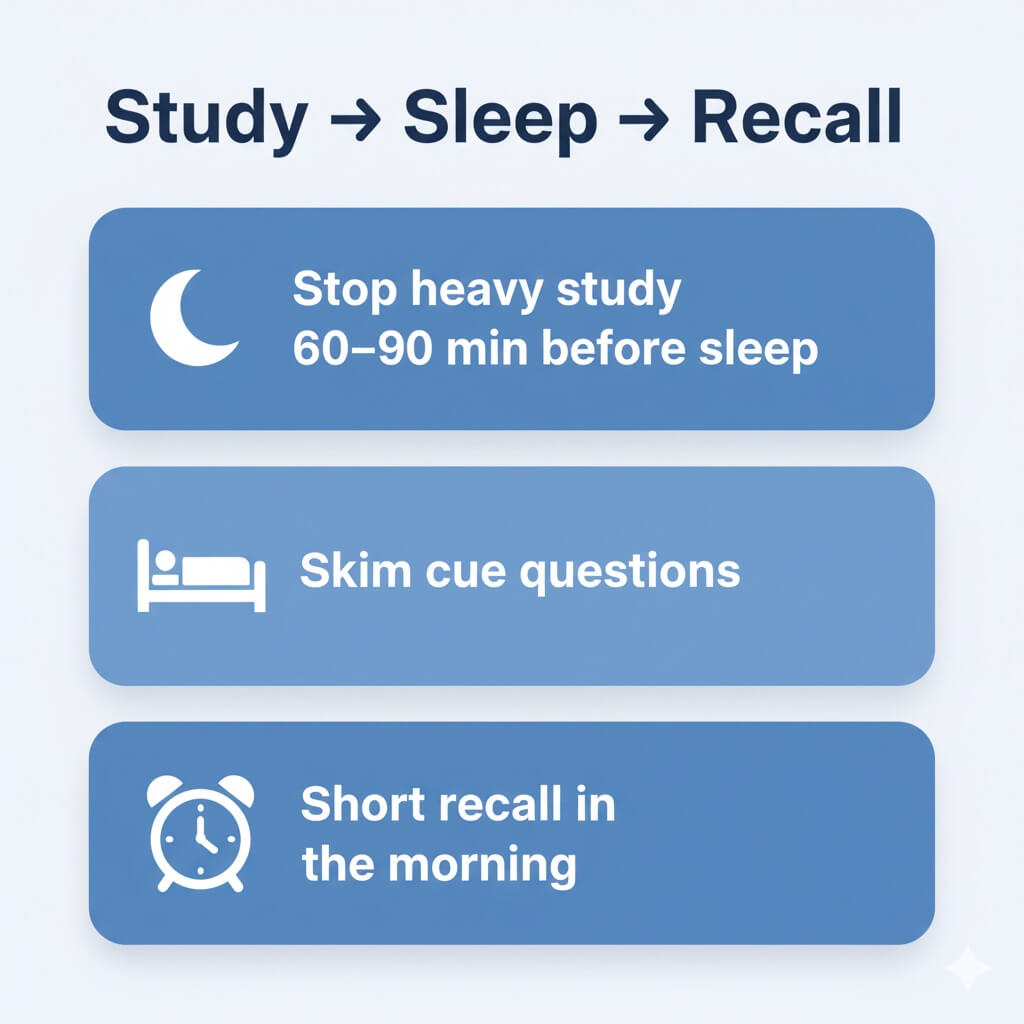

Sleep after study

Post-learning sleep helps memory for facts and skills. If you are short on time, stop heavy study 60–90 minutes before bed, skim your cue questions, and sleep. Even one good sleep after study aids recall more than another tired reread. In the morning, run a short retrieval pass.

Arousal and test performance

A small dose of pressure can sharpen effort; too much can block recall. Find a steady middle. Write a micro-plan, breathe slowly for one minute, and run the next 25-minute block. This idea links to a long-discussed curve relating arousal and performance.

Move a little between blocks

Light movement supports attention and daily performance at school. Short walks or easy mobility between blocks can help you reset without losing time.

Phone control

The phone on your desk can drain attention even when you do not touch it. Put it in another room during each block. Some studies have reported that the presence of a phone can lower available working memory in lab tasks. For a time-pressed learner, removing the device from view is a simple win.

Subject-Specific Fast Tracks

STEM (math, physics, chemistry, computing)

-

Solve more than you read. Spend the majority of minutes on problems.

-

Build a one-page formula sheet. For each formula, add “when to use” and one trap to avoid.

-

Mix variants. Do two problems of type A, then one of type B, then a twist on A.

-

Speak steps aloud. Many errors come from missing a single step; hearing yourself helps you spot gaps.

-

Final 20-minute pass. Run an error log: list the exact step you missed and retest only that step.

Interleaving problem types during practice helps with method selection during the exam. Reviews of mixed practice for similar concepts support this approach.

Conceptual and Social-Science Courses

-

Build two-column compare/contrast tables: concept, claim, evidence, case.

-

After each set, speak a short explanation of one big difference between two ideas.

-

Turn your tables into Cornell cue questions.

-

Use short writing drills: “Explain X in three lines to a friend.”

Essay-Heavy Exams

-

Skeleton first. Thesis, three claims, two supporting sources or examples.

-

Ten-minute outline reps. Draft two quick outlines under a timer.

-

Memorable lines. Write one sentence per claim that you can produce on cue.

-

Source cues. Prepare a short tag for each source so you can cite it quickly during the test.

Princeton’s teaching center encourages practice with old exams and timing yourself with the materials you will have on the day. That advice fits essay planning and quick outlines as well.

Micro-Routines You Can Run Tonight

-

Question sprint (10 minutes): Write six prompts from today’s topic; answer from memory; check; tag red/amber/green. The testing effect is the goal, not perfect notes.

-

Formula sprint (5 minutes): Cover your sheet and write a formula and a one-line “when to use.” Retest the same line after a short gap.

-

Past-paper pair (15 minutes): Solve two items under a timer. Note the exact failure point (definition, step, or cue). This guides the next loop.

Common Traps and Better Swaps

Trap Better swap All-night rereading and highlighting Two short retrieval passes tonight and one in the morning. Perfect notes late at night Fast Cornell conversion with cue questions; retest those cues.

Phone on the desk Phone in another room, timer visible, written micro-plan. Single-topic marathons Interleave related topics to improve method choice.

Use Time Pressure Instead of Fighting It

Short timers help you commit. Write a small target, start the clock, and work only on that target. Avoid constant task-switching. If you need to keep two topics active, alternate in planned blocks rather than bouncing every minute. This rhythm keeps attention steady and still gives your brain the small spacing it needs.

Seven Takeaways You Can Use Tonight

-

Predict likely questions first; study to answer, not to recognize.

-

Run the 90–120 minute loop: retrieval → break → short spacing → interleaving → Cornell page.

-

Sleep after study. Morning recall beats another midnight reread.

-

Move for two minutes between blocks to reset attention.

-

Keep the phone out of sight during blocks.

-

For STEM, solve more; for essays, outline faster; for concepts, compare and contrast.

-

Use simple language in your notes so you can reproduce ideas under stress.

Practical Example: One Evening for a Mixed Exam

6:30 pm: Triage and predict eight questions.

6:40 pm: First retrieval set (math problems + two definitions).

7:10 pm: Micro-break and short walk.

7:15 pm: Compressed spacing pass on the same set.

7:35 pm: Interleave a different problem family and one short compare/contrast table.

7:45 pm: Build a Cornell page with six cues.

7:55 pm: Pack materials; skim cues; lights out on heavy study by 9:00 pm.

Morning (15 minutes): Quick recall from the Cornell cues, then two past-paper questions.

This plan gives you three retrievals on the same ideas with one mixing burst and sleep in between. It fits a workday and still moves the needle.

FAQs

What if I only have two hours?

Run one 90–120 minute loop: target three items, test yourself, take a short movement break, retest the same items, mix a related topic, and finish with a Cornell page. If you have 10 spare minutes in the morning, run one more recall pass.

Do flashcards help at the last minute?

Yes, when they force production. Use question–answer cards that mirror exam prompts and recycle misses after a short gap.

How much sleep should I get the night before?

Stop heavy study, skim cue questions, and sleep as much as you can. Even one full cycle helps. Do a short recall pass in the morning.

How do I study STEM topics quickly?

Spend most minutes solving. Build a one-page formula sheet with “when to use” notes, mix variants, and run a short error-log session at the end.

How can I cut phone distraction fast?

Place the phone in another room during each block. Use a visible timer and a written micro-plan so your attention stays with the task.

Study Tips Students Study Motivation Study Habits