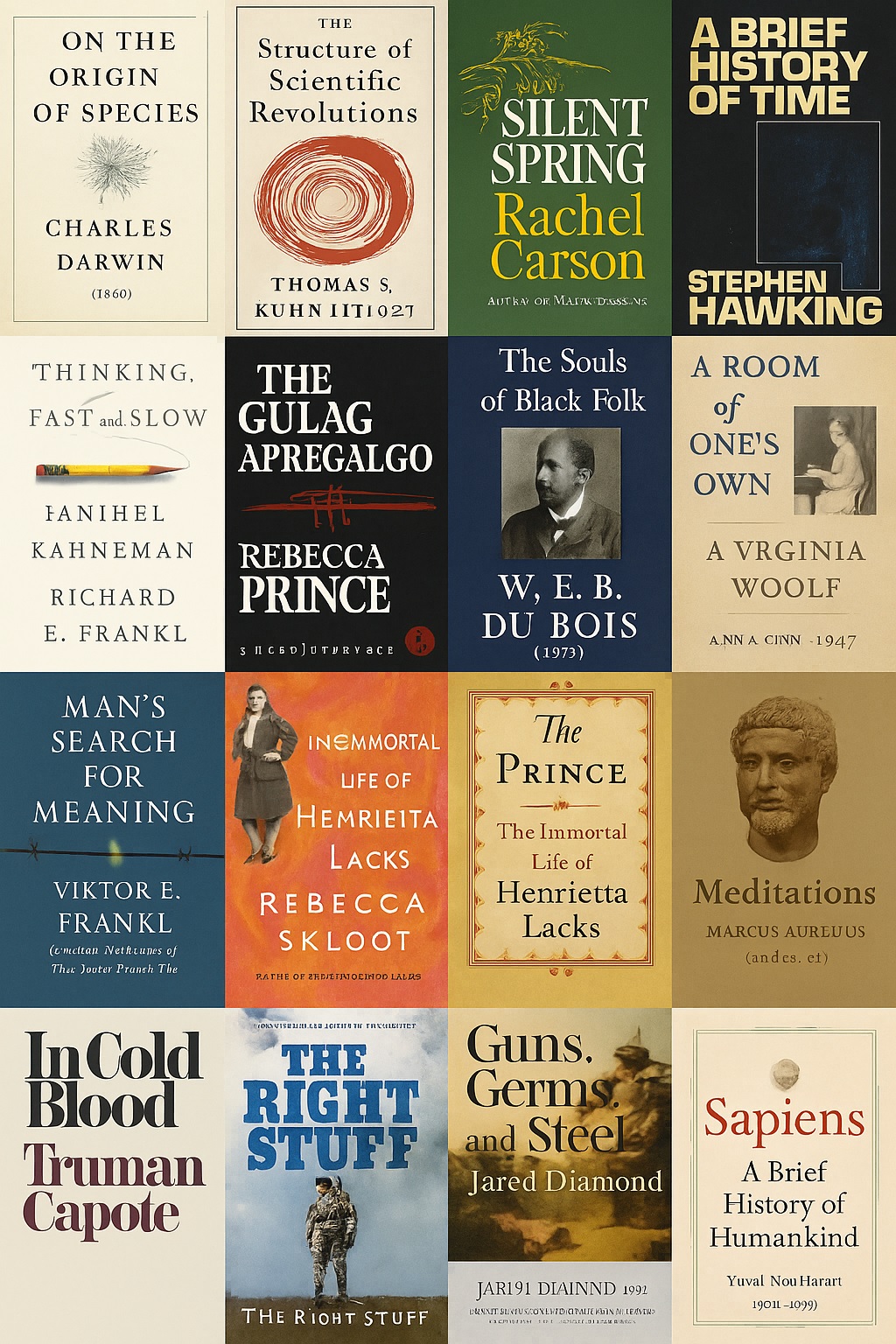

The 20 Best Nonfiction Books of All Time

Why this list earns your time

Readers search for the best nonfiction books of all time to learn, to teach, and to apply ideas. This guide draws on established “best of” lists, academic sources, and reference works. For consensus signals, it aligns with TIME’s “All-TIME 100 Nonfiction Books,” The Guardian’s “100 best nonfiction,” and the Modern Library rankings.

You’ll find clear summaries, reasons each book matters, and practical ways to use them in study, work, and daily life. Citations follow the notes where useful.

Table of Content

- The 20 Best Nonfiction Books of All Time

- Overview & selection criteria

- Who this guide helps

- How to use this reading list

- The 20 best nonfiction books of all time

- Reading frameworks that work (teachers, students, clubs)

- Closing notes

- FAQs

Overview & selection criteria

This list balances four factors: historical impact, scholarly recognition, broad readership, and real-world usefulness. Historical impact weighs policy shifts, scientific paradigms, or movements the book helped shape (for instance, Silent Spring and environmental action).

Scholarly recognition draws on university presses, encyclopedias, and cultural institutions. Broad readership considers sustained reach across decades rather than weekly sales. Usefulness asks a simple question: does the book still teach something readers can apply right now?

Source triangulation aimed for credible, durable references: Britannica and major museum or university sites for context; official prize pages for awards; government, UN, or national institutions for scientific and historical claims; and publisher pages for canonical details.

When an idea remains debated (e.g., gene-level selection), the note stays descriptive rather than partisan. Citations appear where they help a reader verify facts fast.

Who this guide helps

-

Students building a long-term nonfiction reading list

-

Educators selecting class texts with reliable background material

-

General readers seeking must-read nonfiction classics with staying power

How to use this reading list

-

Pick two from science, two from history or politics, two from philosophy or psychology, and one memoir.

-

Read with a simple habit: one chapter, one question, one takeaway.

-

Keep short notes: “Big idea,” “One example,” “How I can use it.”

The 20 best nonfiction books of all time

Ordering blends influence, range across fields, and classroom utility. Every entry gives a one-line case for its place and a quick way to use it.

1. On the Origin of Species — Charles Darwin (1859)

Darwin presents a clear account of variation, inheritance, and selection shaping life over long periods. He draws on fossils, breeding records, and biogeography to show small differences accumulating into large change.

The prose models patient inquiry and invites readers to treat evidence as the center of argument.

Why it matters: Reframed biology with testable mechanisms for change across generations, centering natural selection.

Use it: When teaching evidence, show how observations on the Beagle and later synthesis turned into a theory that still guides research.

2. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions — Thomas S. Kuhn (1962)

Kuhn traces cycles in scientific work: stability, growing puzzles, and abrupt redesigns of core models. Case sketches from astronomy and chemistry illustrate shifts in instruments, language, and standards.

The book helps readers see research as a social practice with rules that evolve across eras.

Why it matters: Popularized “paradigm shift” and explained how normal research meets anomalies that prompt new frameworks.

Use it: In research methods courses, map a current field’s “normal science,” list anomalies, and model a shift.

3. Silent Spring — Rachel Carson (1962)

Carson links observations from farms, rivers, and labs to show how certain pesticides move through food webs and harm birds, fish, and people.

She writes with restraint, pairs stories with data, and gives readers a template for asking careful questions about risk and responsibility.

Why it matters: Sparked modern environmental awareness and scrutiny of pesticide practices.

Use it: Pair a chapter with a public-policy timeline on pesticides and risk communication.

4. A Brief History of Time — Stephen Hawking (1988)

Hawking offers a friendly tour of modern cosmology, touching on big bang models, black holes, and the arrow of time. Short chapters mix brief equations with plain language and thought experiments.

Readers gain a starter map for topics that often feel distant from everyday study.

Why it matters: Opened cosmology to general readers with clear explanations of space-time, black holes, and the big bang.

Use it: Assign a section on time to introduce models and metaphors for abstract physics.

5. The Selfish Gene — Richard Dawkins (1976)

Dawkins reframes evolution through the lens of replicators that persist across generations. Examples cover kin selection, reciprocal aid, and signaling.

Clear definitions and simple models show how cooperation can arise under competition. The closing idea of cultural replication sparked classroom projects and fresh debate.

Why it matters: Advanced a gene-centered view of selection and gave teachers a lens for explaining cooperation via kin selection and ESS.

Use it: Run a simple strategy game in class to show stable cooperation vs. defection.

6. Thinking, Fast and Slow — Daniel Kahneman (2011)

Kahneman explains two modes of thought, one quick and intuitive, the other deliberate and effortful. Memorable experiments reveal patterns in judgment, including anchoring, availability, and framing.

The book offers practical checks that help readers slow down at key moments and make calmer choices.

Why it matters: Distills decades of work on judgment and decision-making; complements economics, education, and public policy.

Use it: Have students label a week’s choices as “fast” or “slow,” then reflect on one bias they noticed. (Kahneman received the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2002 for related work.)

7. The Gulag Archipelago — Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1973)

Solzhenitsyn assembles testimonies, documents, and personal memory to chart arrests, interrogations, transport, labor, and survival within the camp system. Scenes are stark, yet deeply human. Readers meet individuals and procedures, gaining a grounded sense of how policy and fear shaped private lives.

Why it matters: Documented Soviet forced-labor camps, shaping public understanding of state repression.

Use it: Use excerpts to discuss testimony, memory, and moral courage.

8. The Souls of Black Folk — W. E. B. Du Bois (1903)

Du Bois blends history, sociology, and song to describe life after emancipation and the struggle for education and voting rights. He introduces the veil and double consciousness with precision. The essays connect structural barriers with personal striving, giving language that endures in classrooms.

Why it matters: A landmark of African American letters; introduced ideas such as double consciousness to a wide readership.

Use it: Pair the “color line” chapter with current data to connect history and present-day outcomes.

9. A Room of One’s Own — Virginia Woolf (1929)

Woolf argues that creative work needs money, time, and a private door. Through stories, campus walks, and a famous thought experiment about a gifted sister, she shows how conditions shape outcomes. The tone is steady and practical, fit for workshops and writing courses.

Why it matters: Clear case for the material conditions needed for women’s writing and scholarship.

Use it: Invite students to audit their own study conditions and propose small, workable changes.

10. The Diary of a Young Girl — Anne Frank (1947)

The diary records ordinary moments and sudden fear inside a hidden annex. Anne writes about quarrels, study, affection, and hope. Her voice turns headlines into a face and a timetable, helping readers grasp the scale of loss without losing sight of one teenager’s growth.

Why it matters: A personal record of life in hiding under Nazi persecution; preserved as world documentary heritage.

Use it: Read selected entries to discuss voice, adolescence, and moral clarity under oppression.

11. Man’s Search for Meaning — Viktor E. Frankl (1946/55)

Frankl recounts daily life under extreme constraint and argues that meaning supports endurance and moral choice. He describes small acts that protect inner freedom, then outlines logotherapy as a method for turning values into action. Short chapters make reflection and discussion simple to start.

Why it matters: Presents logotherapy and the claim that meaning-making supports resilience under extreme stress.

Use it: Ask learners to write a brief “sources of meaning” list and reflect on one action aligned to it this week.

12. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks — Rebecca Skloot (2010)

Skloot follows the origin of HeLa cells from a Baltimore clinic to labs worldwide. The story weaves family voices, medical history, and lab practice, keeping human context at the center of research breakthroughs. Readers see how consent, privacy, and benefit sharing shape trust.

Why it matters: Connects biomedical breakthroughs with ethics, consent, and equity through the story of HeLa cells.

Use it: Facilitate a short debate on consent practices then vs. now; close with an ethics checklist.

13. The Prince — Niccolò Machiavelli (1532)

Machiavelli studies founding, maintaining, and losing states through clear examples. He separates moral wishes from institutional realities and invites hard questions about means and ends. The short chapters support debates on law, coercion, loyalty, and reputation in courses that analyze leadership and governance.

Why it matters: A concise manual on statecraft grounded in historical cases; useful for discussions of power and responsibility.

Use it: Compare one chapter’s advice with a modern leadership code and surface tensions.

14. The Art of War — Sun Tzu (c. 5th century BCE)

Compressed chapters outline planning, intelligence, momentum, and economy of effort. Maxims stress preparation, clear goals, and attention to terrain and morale.

Coaches, managers, and students adapt the same habits to projects: gather facts, choose favorable conditions, and act at the moment that matters.

Why it matters: Strategy text on information, deception, and initiative; still applied in policy, security, and competitive contexts.

Use it: Translate a principle into a study plan (e.g., “choose ground” → control your study environment).

15. Meditations — Marcus Aurelius (2nd century CE)

Marcus writes private reminders on attention, temper, duty, and mortality. The notes accept limits and point effort toward what can be guided: thought and action.

Many readers use a paragraph a day as a prompt for journaling, correction, and steadier work under stress.

Why it matters: Private notes from a Roman emperor; a compact guide to Stoic practice and self-regulation.

Use it: Start class with “evening review” prompts adapted from Book II or IV.

16. In Cold Blood — Truman Capote (1966)

Capote reconstructs a family’s murder and the investigation that followed with close reporting and crafted scenes. The book sits between journalism and the novel, raising questions about method and empathy.

It stands as a case study for narrative choices when writing about harm.

Why it matters: Set the template for narrative true crime and raised debates about fact, empathy, and form.

Use it: Analyze one scene for point-of-view choices and source ethics.

17. The Right Stuff — Tom Wolfe (1979)

Wolfe portrays the test pilot culture that fed the Mercury program. Dialogue, technical detail, and gallows humor build a portrait of skill, risk, and rivalry.

The book shows how teams create shared myths that steady nerves and how media frames scientific effort for a nation.

Why it matters: Portrait of test pilots and the Mercury astronauts; a record of risk, media, and national myth-making.

Use it: Discuss how narrative shapes public views of science and exploration.

18. Guns, Germs, and Steel — Jared Diamond (1997)

Diamond links domesticable plants and animals, continental axes, metalworking, and crowd diseases with long arcs of settlement and conquest. Tables and maps make comparisons clear.

The thesis gives readers a frame for debates on inequality grounded in ecology, demography, and resource distributions.

Why it matters: Big-picture synthesis on geographic and environmental factors shaping human societies; awarded the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction.

Use it: Create a one-page map-based note linking environment and technology spread.

19. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind — Yuval Noah Harari (2011)

Harari surveys human history from early cognitive leaps to agriculture and large-scale cooperation through shared stories. Themes include money, law, empire, and technology.

The style encourages cross-disciplinary reading, linking biology with culture and ethics. Many chapters end up as lively seminar topics.

Why it matters: A sweeping narrative of human history that invites broad readers into anthropology and cognition.

Use it: Use a chapter to start a cross-disciplinary seminar linking history, biology, and culture.

20. A Brief Case for One More: add what your context needs

Montaigne writes candid reflections on habit, fear, friendship, illness, and reading. He tests ideas against experience, quotes widely, and circles back to questions without pretending to settle them.

The form gives students a model for honest self-scrutiny and for prose that moves with thought.

Many lists end with Montaigne’s Essays for the birth of reflective prose. For classrooms that center research design, some editors swap in a methods classic. If you want the origin point of the modern personal essay, Montaigne stands tall.

Reading frameworks that work (teachers, students, clubs)

-

Three-pass method: Preview headings and key terms; read for claims and evidence; review with two questions you still hold.

-

Claim–evidence–reasoning cards: For each chapter, write the main claim, the strongest evidence, and how the author links them.

-

Compare & connect: Pair one classic with a contemporary text. Example: Silent Spring with a recent public-health report on pesticides; The Prince with an ethics policy in public administration.

Closing notes

Lists change at the edges. New scholarship reframes old debates; fresh voices reach wide audiences. The books here keep teaching across settings: classrooms, book clubs, self-study. They reward slow reading, good notes, and open questions.

FAQs

1) How did you narrow the field to twenty?

By cross-checking major “best of” lists, adding academic references, and asking whether a book still helps readers learn or act today. TIME, The Guardian, and Modern Library offered broad starting points.

2) What should a beginner read first from this list?

Pick Man’s Search for Meaning for a short, moving start; then try The Souls of Black Folk or A Room of One’s Own for social and literary insight.

3) Which titles help with scientific literacy?

On the Origin of Species, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, A Brief History of Time, and The Selfish Gene make a strong sequence.

4) Is Guns, Germs, and Steel still worth reading?

Yes, for a clear environmental frame on broad patterns in history; read it with critics and case studies for balance. It received the 1998 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction.

5) Where can I find reliable background notes for teaching?

Use Britannica for core facts, the Nobel site for laureates, and institutional pages like Johns Hopkins for ethics cases. Pair entries with primary chapters during lessons.

Must Read Books